You came to Korea in the middle of summer, sweating through your shirt and craving something cold—so of course someone handed you a bowl of Korean naengmyeon noodles. Icy, slippery, tangy—it felt like the perfect heat escape. But what is naengmyeon really? Because here’s the thing: that bowl wasn’t made for summer at all. In fact, you might’ve been eating it completely wrong. Before your next slurp, let’s uncover the real story behind Korea’s most misunderstood noodles.

What Is Naengmyeon: History of Korean Cold Noodles That Might Surprise You

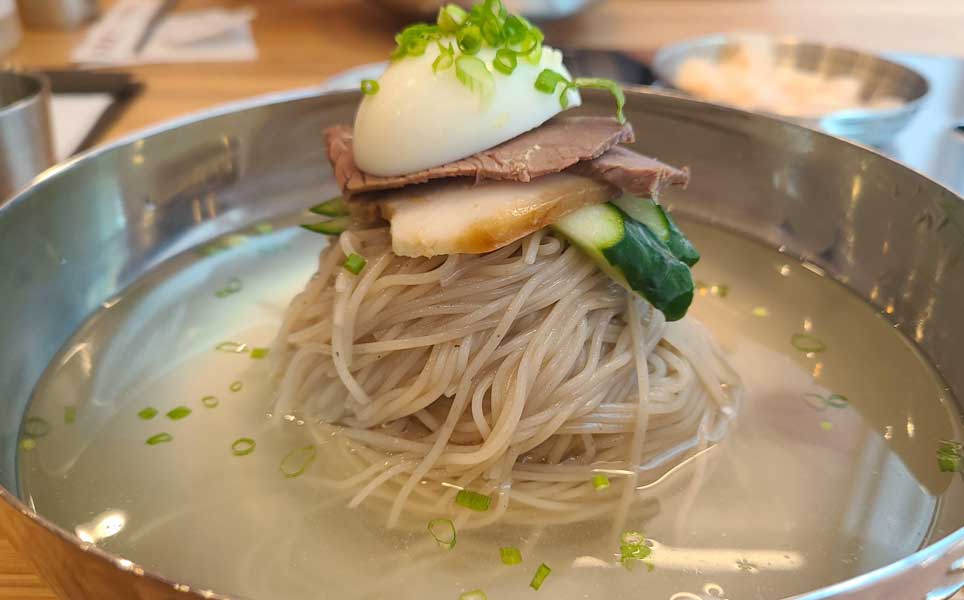

Most tourists know Korean naengmyeon as icy, chewy noodles floating in a silver bowl of broth—garnished with sliced beef, a hard-boiled egg, and thin strips of pear or cucumber. You’ll usually find it after a sizzling plate of samgyeopsal (Korean BBQ pork), offered as a “cooling finish.”

But what’s missing from that experience is the dish’s real identity.

The word naengmyeon simply means “cold noodles,” and it’s been around in some form since the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392). But the earliest named reference comes from a 17th-century Joseon Dynasty text, where a noble scholar described sipping icy noodle broth made from purple omija berries—more tart than savory.

Centuries later, during the late Joseon era, renowned scholar Jeong Yak-yong wrote about hand-pulled naengmyeon in Hwanghae Province, paired with crisp kimchi and winter snow piled a foot high.

Yes—winter. Not summer.

The dish was born in Korea’s northern regions, where freezing temperatures weren’t a problem—they were a feature. Families would make icy broths using snow and cold wells, pairing them with handmade buckwheat noodles. Back then, naengmyeon was a comfort dish for winter—earthy, subtle, and tied deeply to regional identity.

Why You’re Probably Eating a Modern, War-Era Remix of Korean Naengmyeon Noodles

So how did Korean naengmyeon become a summer staple?

It wasn’t until Korea’s first ice plant opened in 1909 in Busan, and later the Korean War scattered northern families to the South, that naengmyeon transformed. Refugees brought their regional recipes—but with limited access to traditional ingredients like hand-fermented kimchi broth or buckwheat flour, many had to adapt.

Enter meat-based broths, flour-and-potato noodles, and vinegar-spiked quick mixes. Artificial seasoning made its way in. What was once subtle and seasonal became bold, tangy, year-round—perfect for the South’s BBQ boom and industrial kitchens.

So that bowl you get at your average restaurant today? It’s real, yes—but it’s also a post-war hybrid built from necessity and modern flavor demands. Understanding that makes the dish even more powerful—it tells the story of a divided peninsula, cultural survival, and the human need to adapt.

Korean Naengmyeon Noodles: Which Type Are You Actually Eating?

Let’s break down what’s in your bowl—because there’s more than one kind of Korean naengmyeon.

1. Pyongyang Naengmyeon (평양냉면)

This is the “original” form—made with buckwheat noodles, served in a cold, clear beef or dongchimi (radish water kimchi) broth. The taste is famously mild, even “bland” by modern standards. But this isn’t a flaw—it’s a feature.

Ask older Koreans, and they’ll tell you Pyongyang naengmyeon is about depth, not spice. It’s about restraint and memory, not shock value.

📍 Where to try it: Seek out restaurants that use buckwheat imported from North Korea, or those who still make dongchimi broth by hand in winter.

2. Hamhung Naengmyeon (함흥냉면)

Born in Korea’s northeastern coastal region, this version uses potato or sweet potato starch noodles—chewy, translucent, and elastic. Often served without broth (bibim naengmyeon) and drenched in spicy gochujang sauce, it’s bold, sharp, and a staple at BBQ joints.

You’ll also find hoe-naengmyeon, where the noodles are mixed with marinated raw fish—usually stingray in South Korea, though it was traditionally sole in the North.

📍 Where to try it: Most Korean BBQ chains offer this version, but for depth, find a specialist shop that makes their own gochujang or uses fermented skate.

3. Milmyeon (밀면)

This Busan specialty was born out of necessity. Hamhung migrants who settled in the southern port city couldn’t find traditional ingredients—so they invented milmyeon, using wheat flour, starch, and pork-based broth. It’s richer, heavier, and uniquely regional.

📍 Where to try it: Busan’s Seomyeon district is lined with legacy milmyeon spots. Go in winter, and you’ll see the original seasonal vibe come alive.

4. Makguksu & Other Regional Variants

Makguksu (막국수), a Gangwon Province dish, uses buckwheat noodles in light kimchi broth with minimal liquid—often tossed like a salad. The deulgireum (perilla oil) version is a fragrant, nutty alternative, loved by locals who want something quick and earthy.

Chogyeguksu (초계국수), from northern regions like Hamgyong, features chilled chicken broth with shredded chicken and vinegar—a gentle but tangy cousin to naengmyeon that’s still relatively under the radar.

How to Eat Korean Naengmyeon Noodles Like It Was Meant to Be

If you want to experience naengmyeon as more than just a side dish to grilled meat, here’s your shortcut to eating naengmyeon with cultural awareness and deeper appreciation, not just a camera clicks:

1. Try It in Winter

Yes, winter. While everyone talks about Korean naengmyeon noodles as a summer thing, the original dish was born in Korea’s freezing North. Locals still enjoy it in cold months—not just for contrast, but because the broth stays icy without melting into blandness.

If you’re visiting in late fall or winter, ask your local host or hotel concierge where you can find a good Pyongyang-style place nearby. The experience feels more honest in a wool coat than it ever will in shorts.

2. Don’t Rush the Vinegar and Mustard

It’s tempting to copy what the table next to you is doing—some Koreans pour vinegar and spicy mustard into their naengmyeon the second it lands. But here’s a travel tip: wait. Take a sip of the plain broth first.

If you’re in a restaurant that makes its broth from hand-aged dongchimi or simmered beef bones, that liquid is the heart of the experience. Taste it as is before adding anything. You’ll better understand what the seasoning is enhancing, not replacing.

3. Ask What the Broth Is Made From

Naengmyeon broth isn’t one-size-fits-all. Some places use beef, others pork, and some even chicken or water kimchi (dongchimi). Each version gives the noodles a different personality—some clean and refreshing, others rich and hearty.

Don’t be shy to ask. A simple “육수는 뭐예요?” (yuksuneun mwoyeyo? – “What’s the broth made from?”) will earn you a smile and sometimes a whole explanation. And it makes a huge difference in what you taste.

4. Look for Clues on the Wall

Korean restaurants often hang their stories—literally. Look at the walls. You’ll often find old photos of founders, regional maps, newspaper clippings, or handwritten menu notes. These aren’t decoration—they’re quiet invitations to understand where the recipe came from.

Some naengmyeon shops were started by families who fled North Korea. Others have been using the same broth base since before smartphones existed. When you pause to take it in, you’re not just eating a dish. You’re stepping into someone’s migration story.

Pro tip: If you’re in a restaurant that only serves one type of naengmyeon and nothing else—that’s usually a good sign.

Your Souvenir Should Be a Memory, Not a Mistake

So the next time someone tells you “Korean naengmyeon is perfect for summer,” smile. Let them enjoy the trend. But when you sit down at a silver bowl, remember you’re not just eating cold noodles. You’re eating a story.

And if you pay attention, your trip to Korea won’t just feed you—it’ll change how you remember taste.

Related Posts

2,286 total views, 5 views today